Every Monday morning, 12-year old Lucas Krukowski boards a school bus at his Cicero home and heads off to school. But, unlike most students, he doesn’t return later that afternoon. Lucas’ parents, Vicki and Dennis Krukowski, don’t see him again until Friday evening.

Lucas is a fifth-grader at the Rochester School for the Deaf, one of 11 private, but state-supported, 4201 schools. They offer specialized academics and related services for students who are blind, deaf or physically disabled. The state established the 4201 designation in 1947 to better coordinate educational goals, monitor student progress, address infrastructure maintenance, and administer adherence to state laws governing board and lodging.

Founded in 1876, the Rochester School for the Deaf is one the state’s oldest 4201 schools. The Krukowskis found compelling RSD’s reputation for balancing students’ exposure to Deaf culture while preparing them to be active members of the greater community.

The Krukowskis adopted Lucas, who was born in China, in 2011. (He is one of four Chinese boys the couple have adopted. They also have three biological children.) In addition to being deaf, Lucas was born with a cleft lip and cleft palate.

Related: Life Changes: Finding out about a child’s disability can be a blow

Dennis had studied American Sign Language and the couple had experience with international adoption, so they felt prepared to help Lucas navigate his challenges. But initially, Lucas was a flight risk. There were also frequent visits to Boston and Rochester for cochlear implant and palate surgeries. Communication was minimal.

A psychologist visited the home to help the family better communicate with Lucas. She suggested that the Krukowskis use pictures to communicate tasks they wanted Lucas to accomplish, and use desired activities as incentives. Lucas soon began associating the signs for these tasks with the pictures. “That’s when things started turning a corner,” Vicki says.

Prior to starting at RSD last year, Lucas attended the Program for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing offered by OCM BOCES in collaboration with the Solvay Union Free School District. It was a deaf classroom in a mainstream school, and everything was interpreted. Lucas made significant progress, but Vicki always knew he would eventually need more educational support. When the Krukowskis decided that Lucas was ready for RSD, his teachers were supportive. But the family’s first request was denied.

“I had to be persistent,” Vicki says. “Total immersion was the best way to meet his needs. He would have been fine at Solvay, certainly. He was in an inclusive classroom. He went to mainstream specials. It’s a good choice and we’re lucky to have that here in Syracuse. But we wanted Lucas to experience Deaf community.”

Vicki asked the committee on special education (CSE) chair for a hearing, and eventually the request was reconsidered.

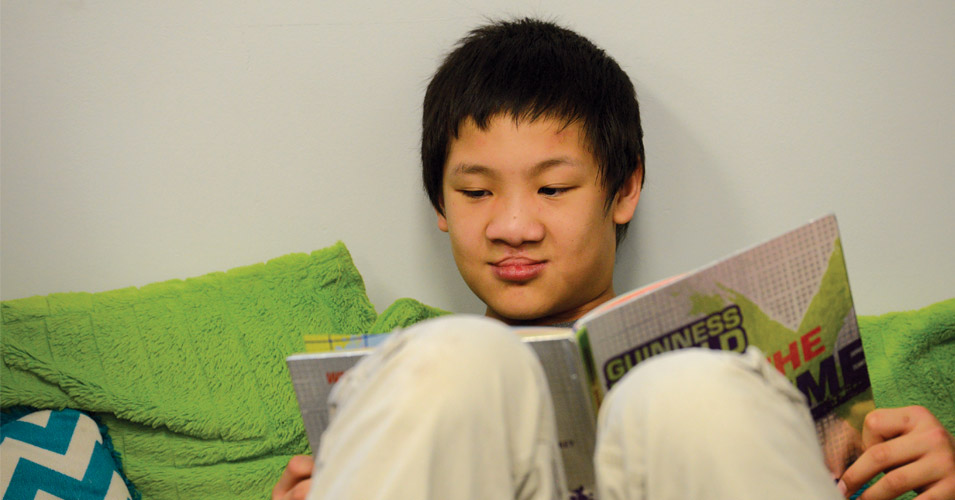

When asked what he likes best about RSD, Lucas signed — and responded in typical 12-year-old fashion. Like many guys his age, Lucas prefers Minecraft and Roblox to reading and writing. He shared that he is currently playing on the RSD volleyball team, and that math and physical education are his favorite classes.

Lucas has flourished in the residential setting and has benefited from the school’s sports and drama programs — opportunities he didn’t have before. Lucas also works with a speech therapist and has regular psychological support.

“His confidence shot up notably in the first year,” Vicki says. “He developed an understanding of what it is to be deaf. I think he likes being in a place that is sort of separate from us. It’s his niche. He’s with his tribe, so to speak.”

Vicki admits she would prefer to be more directly involved in Lucas’ day-to-day life. She and Lucas keep in touch via video calls and texts, and the family attends as many sporting events and school assemblies as they can. His teachers are in frequent contact.

“There is a tradeoff,” she says. “But I know he is getting things in his education that I couldn’t give him here, and an experience that couldn’t be matched living here.”

411 on the 4201s

Before Section 4201 of the state Education law was passed in 1947, the 11 4201 schools were independent. The state’s oldest 4201 school, the New York School for the Deaf in Fanwood, opened in 1817. There are also two state-operated schools: the New York State School for the Deaf in Rome, and the New York State School for the Blind in Batavia.

Approximately 1,500 students currently attend 4201 schools. The state covers the tuition costs—up to $525 per day per student—and the students’ home districts pay for transportation, which is reimbursed though state aid. Support services designated in students’ individualized education programs (IEPs), such as speech therapy and psychological counseling, are covered by Medicaid.

Parents can apply directly to the schools, or at the recommendation of medical professionals or their local school districts. If a student is already enrolled in a district-based program, as Lucas was, parents can request transfer through their child’s committee on special education—the multidisciplinary team that provides services for each special education student.

Prospective students undergo academic and psychological assessments. Vicki Krukowski says parents or guardians are provided with a detailed report of the results.

Antony McLetchie, superintendent of the RSD, says that while there are always financial concerns, the process—by and large—works. But a small student population means that these schools need to be creative to fund anything beyond tuition. It’s also hard for them to offer teachers’ salaries that are competitive with their public school counterparts.

“Our budget is workable right now,” McLetchie says. “But we’re always looking for ways to expand outside partnerships and provide the kinds of experiences that students have in their regular public school districts.”

Some of the schools offer housing for students who cannot commute, or require around-the-clock care. The dorms are licensed by the New York State Office of Children and Family Services. At RSD, the dorm has one adult staff member for every nine students. Currently, 35 of RSD’s 132 students reside on campus during the week

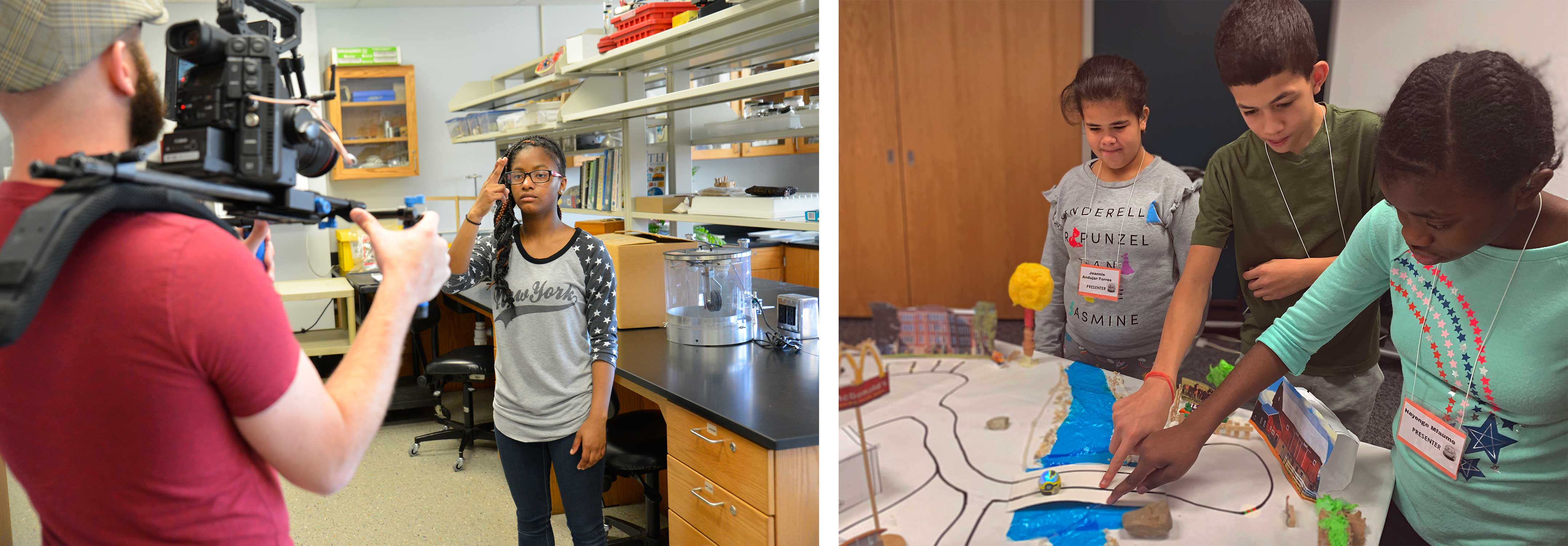

“A deaf student here can be accommodated from their IEP, set future goals, have access to vocational training,” McLetchie says. “We meet the needs of every single child according to their plan, and do so with a strong sense of culture and confidence.”

Both Communities

When Antony McLetchie was appointed superintendent of RSD in 2014, he was determined to move the school forward academically without losing any connection to its rich history. As a deaf person, he understands how important it is for children like Lucas to find their identities. But he also wants them to succeed in today’s job market.

McLetchie’s own education included a mix of public and private schools. He was adopted by hearing parents who understood his individual needs. His mother taught deaf students, and his father was a medical doctor. While the oral method (lip reading and speaking) was a more common form of communication for the deaf when he was growing up in the 1960s, his mother knew ASL.

“I had a deaf nanny who was a great role model, and my mother was always supportive of my needs as a deaf person,” McLetchie says.

McLetchie graduated from a public school with a large deaf population and attended Gallaudet University in Washington, D.C. As someone who has achieved success in the mainstream while maintaining a strong connection with Deaf culture, he’s uniquely qualified to address various concerns families have when they come to RSD.

“The medical community may be telling them that they shouldn’t sign, that they should get a cochlear implant, that these are the advantages of technological advancement. But (doctors) never really share the cultural identity of the Deaf community,” McLetchie explains. “I know there are parents who are reluctant to give up their child to the Deaf community. But that child can be a member of both communities. We want them to graduate with Advanced Regents diplomas, to be fluent in American Sign Language, to be a contributing member of society, and to be a part of the community at large.”

Among the first things McLetchie addressed at RSD was the lack of data on student ability. The school began to use MAP (measurement of academic progress) tests in reading, language, math and science, employed by thousands of public and private schools in the United States. “Intervention is set up if progress is not made,” McLetchie says.

One challenge 4201 schools face that occurs less often in public schools is addressing the diverse academic histories of their students.

“Regardless of where they are when they arrive, we want students to be able to advocate for themselves—to know exactly what their limitations and capabilities are,” McLetchie says. “We need to prepare them for the long term.” Meanwhile, English and ASL are offered simultaneously.

Homecoming

Dr. Bryan Lloyd first walked into RSD when he was 3 years old, graduated in 1982, and currently serves as president of the school’s alumni association. A native of Rochester born to deaf parents, Lloyd says there wasn’t much question about where he would attend school: RSD’s reputation was that widespread.

Lloyd is assistant director of the counseling and academic advising services at Rochester Institute of Technology’s National Technical Institute for the Deaf (NTID). He did briefly attend public school, but he was drawn back to RSD. In his work with the alumni association, Lloyd hears many similar stories.

While RSD cannot offer all the courses that a large public high school can, the school makes every attempt to connect students with specific opportunities. “They were connected to the local public school, so there were other classes that I could take, (such as) creative writing. Those experiences helped grow me,” Lloyd recalls.

RSD is just as committed to helping students interested in vocational training or direct preparation for the workforce, Lloyd says. “They do everything they can to make sure these kids are getting the advantages any other student would get.”

Lloyd says if he could point to one specific thing that most contributed to his success, it would be the opportunities outside of the classroom. “For me, it was the leadership opportunities,” he says. “I was president of the student council, served on the yearbook, the sports were great, the Boy Scouts. It was very important to me that I could be involved in some of those positions that helped me develop my personality.”

After graduation, Lloyd attended California State University at Northridge. He later returned to the East Coast and earned three graduate degrees. By 2001, he was back in Rochester for good.

Lloyd has worked at NTID for the past 18 years, and interacts daily with ambitious deaf students. Through his continued involvement with the RSD alumni association, Lloyd demonstrates what deaf people can achieve.

“My parents are my deaf role models, but a lot of people didn’t have that,” he says. “For me, the alumni, and the association, we feel like our job is to be role models for these students. We are looking to the future.”