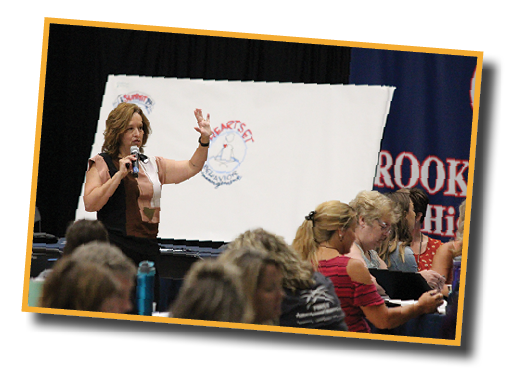

Julie Causton, Ph.D., wants teachers to help students become their best selves. As an educator who has worked at the elementary, middle, high school and college levels, she is passionate about supporting teachers in creating inclusive learning environments. Causton is cofounder of Inclusive Schooling with Kate MacLeod, Ph.D. She’s written or co-written several books on inclusion and teaching. Her first children’s book, The Too Much Unicorn (written with Caitlin Caron), came out in January. Causton consults with school districts across the country on the best ways to make school inclusive.

Causton, 46, is a mother of two and lives in Manlius. She is a former professor in the Department of Teaching and Leadership at Syracuse University. Family Times spoke with her during a break in her travel schedule to discuss creating learning environments that support all students. (This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.)

Having taught at basically every level of education, what led you to focus specifically on inclusion?

Julie Causton: It was a cumulative process. What I noticed early on in my career was that the more a part of the community a student was, the happier they seemed, the more fulfilled they seemed, the more social interactions they seemed to be having. So, I started to look at that pattern of exclusion related to disability, and also the patterns of inclusion.

The more I learned, the more on fire I became about inclusive education. I still see myself as a learner in that every school I’ve been in and every district that I’m in, I’m learning from and with teachers about best practices.

I went to school in a time when students with disabilities—especially significant disabilities—were educated elsewhere. What is fun for me is to look at the difference now and see that people with disabilities deserve a rightful place in our communities and in our schools. Opening the door is the hard part. But, once it’s open, it generally stays open because educators and administrators see the power of what happens when we rethink schools for kids.

Educators and administrators generally want inclusion. But there is a tendency to label students in the rush to get them the support services that they need. What can be done to help educators and parents with that?

JC: I believe really strongly that supports are portable and should be brought to students instead of bringing students to supports. It’s about learning how to differentiate. So, if I’m a general education fourth-grade teacher, I understand that the content is challenging, but I need to know how to differentiate that content to give students access points. If kids can’t read it to decode its meaning, then we have to give them new ways to learn that information. They need to listen to it—maybe have a peer read it to them. We just have to start thinking more broadly about what’s possible.

In New York state, and in lots of places, we’re very deficit-focused. We are constantly looking at how far below the norm a student is. Inclusive education forces us to flip that around and look at a student’s strengths. The very nature of inclusion forces us to rethink pretty much everything about teaching and learning—for the better. A lot of the things we do in special education are just good practices for teaching. When we no longer separate humans by disability, then we start sharing those practices. When we share those practices, better things happen for more kids.

You talk about the role of the classroom teacher in your writing. In a typical or special ed. classroom, they have to evolve in order to best accommodate inclusion. Where does that begin?

JC: It’s societal. I think we can start at any place. I’ve seen parents be the catalyst for it, I’ve seen a teacher right out of Syracuse University be the catalyst for inclusion. I’ve seen an administrator who says, “This is what I believe.” I’ve seen students who say, “I don’t like it when our friend goes down the hall. We think he can be in this class with us.” Systemically, I see a lot of hope when I think about teacher prep programs like Syracuse University that have dual licensure—students have general and special education licenses when they graduate, and they know everything there is to know about inclusive education. I taught there for 14 years and I know they are changing schools and systems in profound ways. On the other side of it, I teach administrators. George Theoharis (SU School of Education professor) and I have a summer leadership institute for administrators from all over the country. (Inclusion-fest 2019 took place in August at Syracuse University.) They learn how to create more inclusive schools. They often go back to their schools and start to look closely at their systems. I often equate it to Brown v. Board of Education. In 1954 we decided that you can’t segregate people by race, and yet we still think it’s okay to segregate people by disability in our practices. Nobody intends to do that, but just look at our classrooms.

Do you find that the current emphasis on student and teacher performance creates barriers to inclusion?

JC: I think high expectations are good for everybody. I think the people who become successful at inclusive education are those who can learn easily how to give students access points and differentiate the material. When you have a lot of lockstep teachers just covering content, kids can really struggle. But when there are teachers who have a wider array of tricks and skills, then it’s not an issue to educate kids—even when expectations are high.

So why aren’t administrators embracing inclusion on a wider scale?

JC: When you lead a change like this, the resistance from some administrators is pretty significant because they are being asked to do things they may not feel comfortable with. I’ve studied the change process, and there are all sorts of steps that humans go through, and none of that is pleasant to be on the receiving end of.

Is cost a factor?

JC: It doesn’t cost more money to teach inclusively. We move resources from segregated classrooms to inclusive ones. Schools don’t get more teachers, or more paraprofessionals, or anything like that. It is costly in terms of energy. It takes a lot of energy to move a system and to get everybody on board, skilled up, and able to meet the needs of all learners, and then to problem solve when things don’t go well. But the rewards are great. All educators, I believe, have come to this work with the right intentions: to do right by kids. The problem is, our systems aren’t always set up to do the right things for kids. When educators see it, they know it, and the resistance dies down and the support for the work continues.

Parents want their kids to be as included as possible. Inclusion takes some of the stigma out of any kind of diagnosis. Has your research confirmed that?

JC: I would say so. Belonging is key before students can learn at all, so that stigma is of course very big. But even bigger than that is the fact that all kids need to feel like they are part of their school community, and moving away from a school community has a pretty negative impact on self-esteem and all those other pieces. Parents intuitively know this and feel it themselves. That’s one reason why they are fighting for inclusive education.

I’ve been to many different programs and placements, and although some of the teachers and experiences for the kids are really good, I have yet to see something that is so fabulous and specialized that it couldn’t be replicated in their home district. They could all be brought to students’ districts so they don’t have to deal with the stigma and the problems with belonging that can cause students to not be able to learn for years at a time.

In New York state, a typical elementary school might have a couple segregated classrooms. Within those, there might be six or seven adults. If we redeploy those resources to general education classrooms, we can cover a lot of places so that any kid who struggles with anything has adult support. When it is done beautifully, they provide all kinds of supports to all kinds of kids. It’s better for every classroom to have multiple adults. The problem is we are keeping all the resources in rooms, and I have yet to see a room where I thought it was worth the stigma and sacrificing the belonging.

You worked with Salem Hyde Elementary School in Syracuse on inclusion.

JC: Salem Hyde was very successful with inclusion even before we got there but became even more inclusive. Their students with disabilities saw really lovely academic gains. We worked with Roberts School also—probably 15 years ago. Things have probably changed or morphed in some way, but we worked closely with them for three years at a time.

How does being a parent influence your work?

JC: I am a parent of two kids, one who happens to be legally blind. Ella, my daughter, is 14, and my son, Sam, is 16. I was in this field before Sam came along. Even before I was a parent of a kid with a disability, I was very empathetic to parents. When I was a teacher and I would be at an IEP (individualized education program) meeting, I sort of put myself into their shoes and was like, “Whoa. All these people come into a room with all this paperwork to tell parents just how many standard deviations below the norm their child is?” I watched parents sort of shut down during that process because it was a different language, really, and because it was so deficit-based.

When I had a child with a disability that became even clearer to me. In my professional life, I am considered to be an expert in disability and inclusion. But then I sat at a table where I wasn’t really seen as an expert in much. I was surprised by how quickly the power structure of the IEP meeting itself took over, and how quickly my ex-husband and I were kind of silenced. I kept thinking, “I have a Ph.D. in special education. I should know this stuff. I should be able to stand my ground at a meeting.” But when they are talking about your child, it’s definitely quite emotional. It just really bolstered my belief in supporting families.