When Amy Hysick was growing up in North Syracuse, she developed a passion for learning and adventure. She was an active girl who loved the outdoors, so no one was surprised when she decided to study science in college.

The surprise came a few years later, when Hysick, now 42, followed her parents, Jim and Judy Sonich, into teaching.

Today, Hysick, the oldest of three sisters, teaches science in the Cicero-North Syracuse School District. Her parents taught in the North Syracuse district for the entirety of their careers: 68 years combined. And last fall, they were sitting in the audience in Albany when their daughter accepted her award as the 2017 New York State Teacher of the Year.

“I was always into science,” Hysick recalls, describing a childhood spent catching frogs and learning to fish. “Dad would go fishing. I was the gross kid who would poke the fish eyeballs. I knew the internal anatomy of a fish before I went to kindergarten.”

Jim Sonich was a sixth-grade teacher. Judy taught German at the junior high and high schools. When they began teaching, Jim was one of the few male teachers in the district.

“Even in college he would talk about how he didn’t think it was good that students were being taught only by female teachers all the way through the elementary grades,” Judy says. “He really believed in having male figures in the schools.”

“Guys are different,” Jim says. “They approach emotions differently. They approach teaching styles differently.”

Read: “Early-elementary teachers get creative to foster good reading habits”

The close proximity was never an issue for the couple. “I just stayed out of his way,” Judy jokes. But for their daughters, it was a little more difficult.

“I never got in trouble or got detention because I lived in fear of my parents’ disappointment,” Hysick recalls with a laugh. “I never, ever wanted that. And if I did put any toe out of line, they knew before I could tell them.”

Looking back, Judy Sonich admits having your parents as teachers in your school might not be a child’s preference. “Amy did feel as though there were more eyes on her in the buildings with both of us working there.”

After graduating from Cicero-North Syracuse High School, all three Sonich sisters settled in the area. They have eight children among them. “Our family’s roots run deep in this school district,” says Hysick, who lives in North Syracuse with her husband, Chris, and daughter, Tessa, 7. “And now, I will be the eyes of the building for all of our offspring.”

Reflecting on her school years, Hysick says there was more inspiration than trial. A healthy respect for teaching, and those who do it, was nurtured.

“Educators were always role models,” Hysick says. “Education was what the adult conversation was in the house most of the time.” But when it came time to go off to college, Hysick’s plan was pre-med.

As a junior at Binghamton University, Hysick experienced a turning point taking a microbiology class. Her professor saw “something” in her approach to the material and asked her to teach a section of the lab the following semester.

“It flipped the switch all the way in my head,” Hysick recalls. “I loved doing it.”

After completing her undergraduate degree in biology, Hysick informed her parents that she would be going to graduate school for secondary education, not medicine.

“It was a little bit of a shock,” Hysick says. “Going into ‘the family business’ wasn’t discouraged, but it wasn’t encouraged. We were encouraged to do whatever it was we wanted to do.”

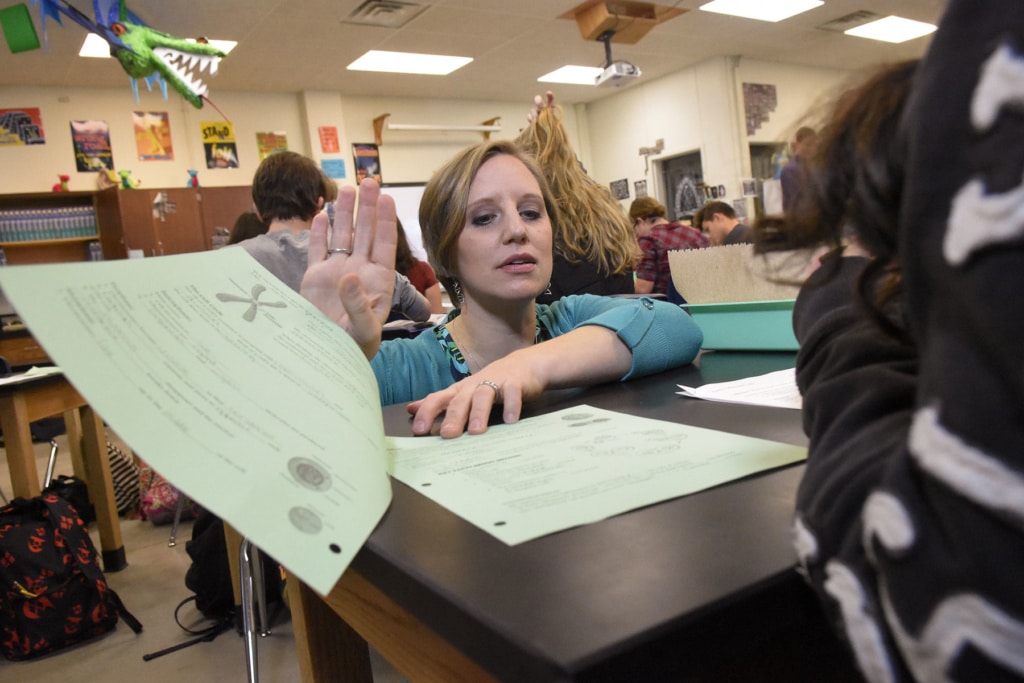

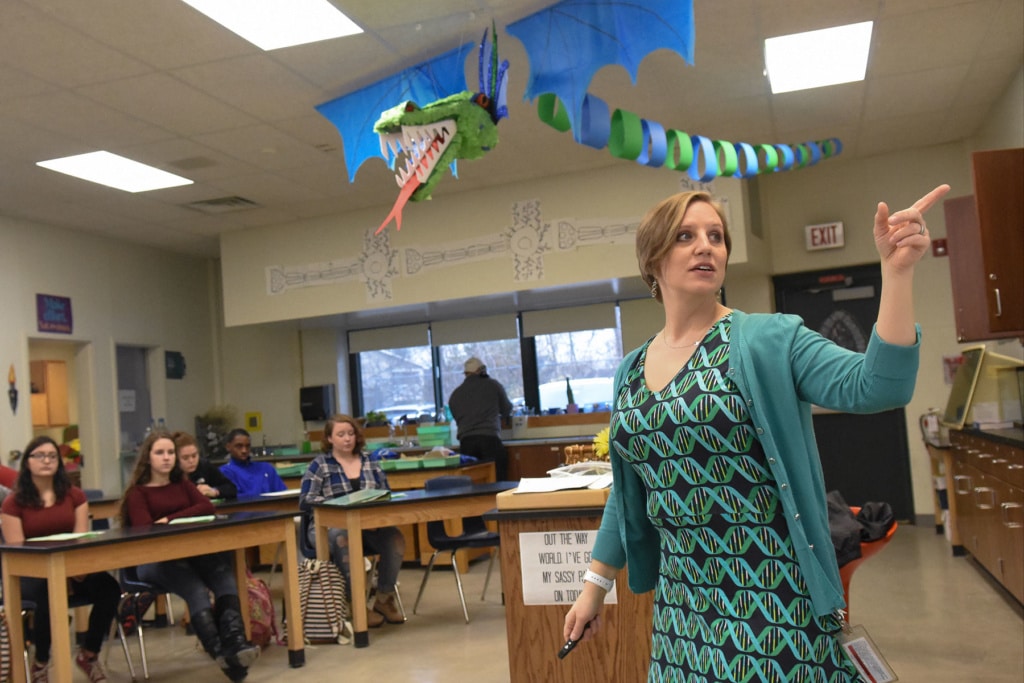

Hysick’s sprawling classroom shows the depth of her commitment to her subject and her students: There are live animals in habitats, including a bearded dragon and three snakes, and Pinterest-worthy displays demonstrate her crafty side. Creating a welcoming space is just a small part of how Hysick tries to connect with her students.

Hysick co-taught a Science Explorations class in addition to three sections of Regents Living Environment last year. She has worked hard to get students to embrace a growth mindset; assignments can be revised, and tests can be used as opportunities to revisit material until students are comfortable in their understanding of it.

“We tried a lot of things to boost student engagement,” Hysick says. “There (were) kids in my science explorations class who (were) disinterested or disengaged. They don’t want to be here. They don’t want to learn science. It’s a graduation requirement. The special ed. teacher who co-teaches with me (Jeff Colasanti). . . we brainstorm trying to figure out different strategies.”

One strategy was to craft a lesson around a Hollywood movie: looking at fact and fiction. “By using that, we have found that some of the students who were the most disengaged, who always were looking at their phones, are now the ones with their hands up first. They are the ones asking questions.”

“It’s a way to look at learning as authentic experiences,” Hysick adds. “It’s real-world applicable.”

Using technology is another key to Hysick’s success. She is a big fan of ZipGrade, a grading app with real-time feedback on quiz results that can be shared with students. Hysick can then tweak lesson plans based on the information gleaned from those results. The feedback Hysick’s students get enables them to “study smarter, not harder.”

“The most important message I want students to take away from my class is that you learn from failure. It’s part of the learning process,” Hysick says. “When you get something wrong, you’re driven to find out why. It’s a constant refining process.”

Hysick applies that same approach to her own role. As changes to the New York state learning standards and Regents core curriculum have come down the line, Hysick has changed her lessons and how she presents the material. Relationship building, she says, is an important element of effectiveness.

“It isn’t the curriculum that has changed the most,” Hysick says. “It is how I approach planning. It is how I approach interactions with students. It is how I set up my classroom. Those sorts of strategies have changed more than anything else.

“I am not the same teacher I was when I started teaching—by far. I’m not even the same teacher that I was two years ago. I’m always learning from my students how to be better. And I’ve made my mistakes, too.”

Hysick considers her parents two of her most important sounding boards. But Jim Sonich says they are rarely compelled to give advice.

“Since we are out of it now, our input is minimal,” he says. “I’m in awe of how different teaching is now, and of what Amy does.”

Judy Sonich wonders how much value the current emphasis on teacher evaluation contributes to the student experience. But observing Hysick’s enthusiasm makes Judy think many things haven’t changed.

“What strikes me is that teaching, no matter what the subject, can be creative,” she says. “You can revamp your whole approach every year.”

Judy says Hysick inherited her dad’s sense of humor and stage presence, which have served her well in the classroom. “You have to feel comfortable in your own skin, and you have to entertain a little,” she says. “She has all of that as well as the love for her subject.”

Hysick is finishing her role as a state ambassador for the teaching profession this summer. A new Teacher of the Year will be announced in September. While she appreciated being chosen to represent her profession in this way, Hysick’s biggest rewards come from the feedback she gets from former students. She keeps what she calls a “happy file” of notes and cards. Breaking it out at the end of a tough day can reaffirm her commitment to the vocation her parents modeled for her while she was growing up.

“It’s the kids who come back and visit,” Hysick says. “There is really nothing better than that. Just knowing you made a difference—even just a little bit—that’s my reward.”