“Remember when my school supplies consisted of some folders, pencils and crayons?” my daughter said, laughing, as we laid out our cart full of this year’s supplies. “I sure miss those days!”

She’s a freshman in high school now, my girl; her brother is a junior. These years they will see firsts that make learning to walk and talk seem like, if you’ll pardon the pun, child’s play. They will learn to drive, have first loves and, likely, first heartbreaks. Their bodies will change in ways that may confound them. Their circles of friends will change as personalities and interests mature. They may find their expectations—academically, socially, athletically—challenged on every level.

As I watch them navigate these years, I remember every single emotion each of my children is feeling at any given moment, because I felt every single one when I was their age.

And I wish to God I could make it easier for them with what I’ve learned since.

With all of the technology at their fingertips, for example, the pressure to fit in is constant. I wish I could tell them that popularity does not define them as worthy, and that the right clothes do not make them better people. What I’ve learned is that what makes us worthy, what makes us good people, are things like integrity, kindness, empathy, and our willingness to love and help others.

With academic pressures at ego-crushing levels, I wish I could tell them that grades aren’t part of some permanent record that will dictate the course of their lives, that state tests and SAT scores are not really an indication of who they are as people. What I’ve learned is that what makes us intelligent is our capacity to learn, and more importantly, our desire to.

With the societal expectation of year-round athletics, I wish I could tell them they don’t have to be “the best” at the sports they play, and their self-esteem should not be tied to trophies and first-place finishes. What I’ve learned is that what makes us good athletes—what ensures that we keep playing and remain active—is our sense of sportsmanship and the simple love of the game.

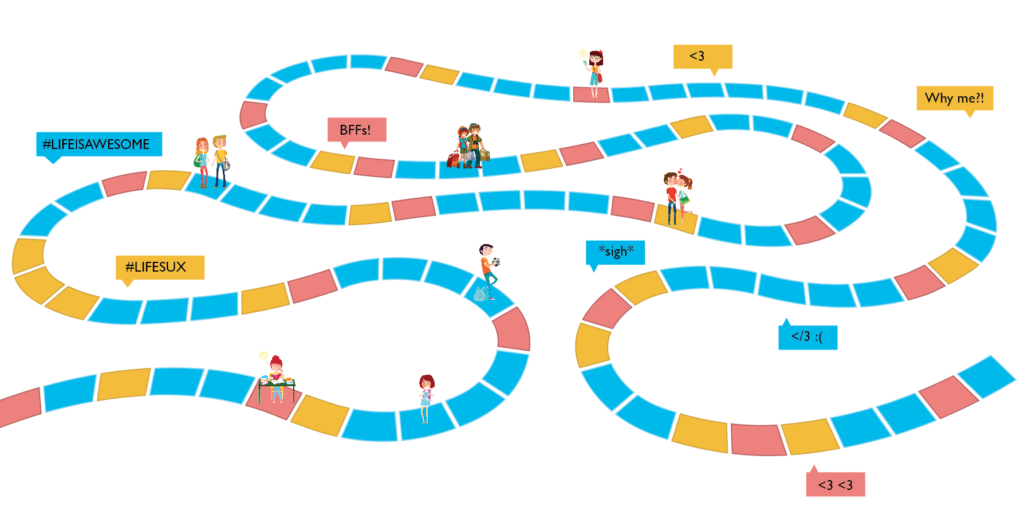

With their own drives to achieve, I wish I could tell them not to think about what they want to do with their lives, but what they want to do first; that by focusing on one thing, they’re not giving themselves permission to change direction if it doesn’t work out as planned. What I’ve learned is that life is a journey—that we’re allowed to find what might make us happy, to try it, and if it we don’t like it, to move on to the next thing.

With the physical changes and self-awareness that accompany puberty, I wish I could tell them not to stress about acne and periods and sweat and bodily functions; that everybody has something that bothers them about themselves, whether it’s physical, emotional or mental. What I’ve learned is that there is no perfect being, and that as long as we have the potential to manage our challenges, things will work out.

As their mother, I wish I could tell them all of this, but these things can’t be told: They must be learned. I have to let them live these high school years just like I did, so they can learn just like I did.

And what I’ve learned is that my job is no longer to prevent them from getting hurt, or to stop them from making bad choices or wrong decisions. No matter how hard it is, my job now is to encourage them to get back up when they’re down, because all of these life lessons are going to help them become the magnificent adults they’re on their way to being.

I look down at the cart full of school supplies, and remember when a hug was all it took to assure my children that everything would be OK. And I smile so that I don’t cry.

“I miss those days, too, baby girl,” I tell her. “I miss them, too.”