To discover the value of a dollar—or several—young people need opportunities to learn about saving, spending, borrowing, and how to balance their needs and wants.

In Central New York, students are taking advantage of programs that develop their skills and the knowledge needed to make informed choices about money and other financial resources. This knowledge is known as “financial literacy,” and many kids don’t have it.

More than a fifth of American teens lack basic financial literacy skills, according to the Program for International Student Assessment. Without a deep understanding of how money works, young people (and their parents) are vulnerable to predatory interest rates on credit cards and online “get rich quick” schemes. What’s more, teens stand on the cusp of making money decisions that can affect them their entire lives, including whether to attend college and how to pay for it.

Thom Dellwo is financial education coordinator at Cooperative Federal Credit Union in Syracuse. He teaches financial literacy to students and adults and supervises branches of the credit union that operate at high schools in Syracuse.

“The goal is encouraging students to form a relationship with a financial institution,” he says, pointing out that people who don’t have a bank or credit union often cash paychecks at corner stores or check-cashing services that charge a fee. “They may have to pay a $10 fee to cash a check from a part-time job,” he says. Those fees quickly eat up savings that can help a young person get ahead.

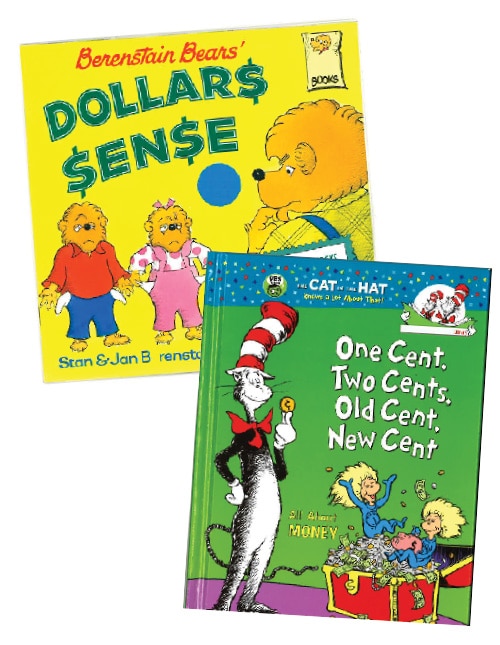

But the ABCs of financial literacy can be learned even before young people are earning paychecks. First-graders at Solvay Elementary School get a lesson in money on Tuesday mornings during the school year when one of several volunteer employees from Solvay Bank comes by to read to them, says Michele Fernandez, vice president, enterprise risk manager and community reinvestment officer. The books are specific to money and budgeting. They include One Cent, Two Cents, Old Cent, New Cent, a Cat in the Hat book, and The Berenstain Bears’ Dollars and Sense.

After the storytime, the students discuss the book. Amber Jaquin is a Solvay Bank branch manager in Cicero and an assistant vice president. She’s read books to the Solvay first-graders several times. They’ll talk about where their parents bank and share things such as, “Mom doesn’t use cash, she uses a debit card.”

Cooperative Federal Credit Union offers savings accounts to children at Edward Smith K-8 School in Syracuse. Since 2008, children there have been able to put away money each week, developing a savings habit and accumulating money toward a goal.

Dellwo also offers a financial literacy class to elementary-school age children at the Southwest Community Center. He hears all sorts of savings goals from the children, who collect their money in Styrofoam containers: a video game system, a puppy, a car or a helicopter—and even a mansion.

At the three Syracuse high schools where Cooperative has branches, students are encouraged to label their savings account according to what they are saving for. An iPhone is a popular account label, Dellwo says. Other students are saving for a car, or at least a down payment for one.

Some young people are facing more immediate needs, putting money aside so they can help their parents through rough financial times. One student was saving so she could buy her mother a spa day after a particularly trying period.

Liverpool High School students, as well as teachers and staff, can bank at Edge Federal Credit Union’s branch that operates in the school cafeteria, says Theresa Lotito-Camerino, the credit union’s manager/CEO. The branch is staffed by student volunteers who gain experience with money by acting as tellers.

The credit union is also active at John C. Birdlebough High School in Phoenix. It has a branch open there on Wednesdays and provided a financial literacy simulation program that challenged students to budget properly.

The Mad City Money simulation put together by Edge at Liverpool High School draws more than 100 students to the gym, where a random drawing gives them a set imaginary income that they get to spend. They go from table to table, meeting with adult volunteers with whom they negotiate necessary and not-so-necessary purchases—a car, childcare, clothes, furniture, housing—and pay by debit card. The goal is to finish up with some savings.

Those who end up in deficit have to go back and renegotiate, maybe even return a high-end car for something more practical. “They were shocked at how far their money didn’t go,” says Casey Thurston, student branch coordinator for Edge.

Students were tested on their financial literacy and received their grades expressed as credit scores. “Some of these kids were on the ball,” says Lotito-Camerino. “Half had A-plus credit scores.”

Anna Leung, 17, is a senior at Liverpool High who volunteers at the credit union branch. She originally volunteered because she thought she wanted to be an accountant someday. She’s changed her mind about her career goals (she is now interested in art and design) but has learned a great deal about finances. She was able to use that knowledge to convince her parents to let her get a debit card, pointing out it was safer when she was traveling.

“I like it,” she says of having a debit card. “I just had cash before,” adding, “I just feel more financially responsible.”

Those who talk with teens about finances say debit cards are key to them. “How soon can I get a debit card?” they’ll ask Dellwo. The main reason for that is so they can shop online, Dellwo says.

Jesse Davis, an eighth-grader at Expeditionary Learning Middle School in Syracuse, will use cash to buy a prepaid card so he can make online purchases. A saver, Davis regularly sets aside money for specific purchases.

He saved money to purchase an Xbox 360 game console with Grand Theft Auto IV. He makes money by collecting returnables, babysitting and doing yard work. He managed to save $30 and sold his old Wii game console for $40. He found the console he wanted, used, for $73 at the Central New York Regional Market’s Sunday flea market. His father Jeffrey Tamburo chipped in $3 to make the purchase possible.

One recent day, Davis admitted that he was down to about $1 in savings because he had just bought a new case for his phone, the phone on which he keeps an app for budgeting and another for calculating interest. The first one helps him keep track of his spending so he has money to pay his phone bill and his bill for the video-streaming service Hulu. The latter helps him when borrowing from his parents.

“Sometimes I’ll buy something with my dad’s credit card and I’ll pay him back,” he says. The interest rate app helps Jesse figure out just how much he’ll owe.

“I’ve always been interested in money and finances,” he says, recalling days when his father Jeffrey would use budgeting software from personal finance guru Dave Ramsey. “I would look over his shoulder,” he says. He would also listen to Ramsey’s podcasts.

That level of financial interest isn’t something every student has, says Rebecca Rose, director of financial aid at Onondaga Community College, but she doesn’t blame students. A 22-year veteran of financial aid work, she says the parents of students often had little understanding of financial matters themselves, in part because widespread consumer credit didn’t exist until the 1970s and 1980s. “We were never taught,” she says.

To bridge that knowledge gap, OCC has a number of financial literacy programs available to students. Rose says they include programs presented by AmeriCU, the credit union with a branch at the college. The Department of Residential Life hosts other programs and there is an online program through the State University of New York.

A new offering comes through the financial aid office. Last year, the college invested in 10 different professionals from around the college so they could become certified as personal financial managers, Rose says. They now provide one-on-one counseling to students.

Rose says students are often grateful for the chance to get practical information about finances. Some ask if they can come back for another appointment. They definitely can, she says.

“We want smart borrowers,” Rose says. Students will be asked to look carefully and see if they really need to take out a loan. Perhaps they can work extra in the summer and earn enough to cover their expenses, or maybe they can just borrow less.

The counseling includes teaching them about credit and how to use it wisely. Some students come in thinking any borrowing is bad, Rose says. Others don’t understand the burden they are taking on. They learn about credit scores, borrowing and how to manage their credit so that when it’s time to buy a car or a home, they get the best interest rate available. “We talk about saving money so you don’t have to take out loans,” she adds.

Liverpool High School graduate Benjamin Tamber understands the importance of savings. “Pay yourself first,” he says. “I pretty much live and die by that.”

A business and accounting major at Villanova University in Philadelphia, the 19-year-old sophomore says he has always been frugal and learned from his parents to pay credit card bills on time and put money aside for planned purchases. He saved his first paycheck from his summer job knowing he would need it to pay for books at college.

Tamber volunteered at the Edge credit union branch at his high school when he was a student and worked at the main branch in the summer. Yet despite his major and his experience with a financial institution, he was facing a challenge as the fall semester began. The bank he uses at college—he chose it for access to ATMs on campus—had unexpectedly charged him for not using the account during the summer months.

That’s not unusual, in the experience of Thom Dellwo of Cooperative Federal Credit Union. He sometimes hears from students about their families’ unpleasant encounters with financial institutions.

“Make sure you find an institution you know is trustworthy,” says Tamber. He’s a fan of credit unions. “I’m really passionate about it,” he adds. “I know that they are looking out to try to help the member.”

Julie Pento is a senior at SUNY New Paltz who has worked summers at Edge. She says she learned a lot during the summers and wishes she had created more subaccounts to help her save for more expenses along the way. She also wishes she had understood earlier that there are people willing to help her understand the financial questions she faced getting ready for college. “I wish I knew how approachable everyone was. Financial things feel very overwhelming at that age.”

Of course, financial questions don’t end when school does. Joe Leo, vice president and financial consultant at DLG Wealth Management in Utica, meets with students at Colgate University as part of the school’s Real World Series. He says that seniors in their last weeks of college have basic questions about budgeting and paying bills. He has shared with them some uncomplicated rules about paying off credit cards each month, not wasting money using ATMs that charge fees, avoiding credit cards that charge annual fees and not buying what they don’t need.

“All of us have two people inside of us,” says Dellwo of Cooperative credit union. “One makes rational plans and one is irrational and says, ‘I want it and I want it now.’ Learning helps us to control that wild and crazy side.”

Why Financial Literacy Matters Now

- It wasn’t long ago that financial literacy wasn’t even a thing. People had money or they didn’t, and they spent accordingly.

- Today, the wide availability of credit cards, lines of credit, payday loans, income-tax refund loans, student loans, car loans and home-equity loans has made understanding money, budgeting and borrowing a skill that can determine success the same way education can.

- Students who leave college owing student loans are significantly less likely to own their own homes, according to a Federal Reserve Bank of New York analysis. While 31 percent of graduates with associate’s degrees own their own homes, only 24 percent who have student loans are also homeowners. Those with no college education have a home ownership rate of 22 percent.

- Recognizing this change, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, widely known as the OECD, added financial literacy to its projects in 2003 and uses the Program for International Student Assessment to measure the financial literacy of people in different countries. Thousands of students have been tested around the world. Findings from 2015, released earlier this year, offered some insights:

- Financial literacy depends in part on having skills in math and reading. Those who do better in math and reading do better in financial literacy.

- Financial literacy is not gender dependent, although it is stronger among females in some tested countries and among males in one (Italy). In the United States, there was no statistically significant difference in financial literacy between boys and girls.

- Scores for financial literacy are lower for those who have immigrated or are the children of immigrants, compared to natives in their countries.

- Economic advantages tend to indicate greater financial literacy. There was a strong correlation between student socioeconomic status and financial literacy.