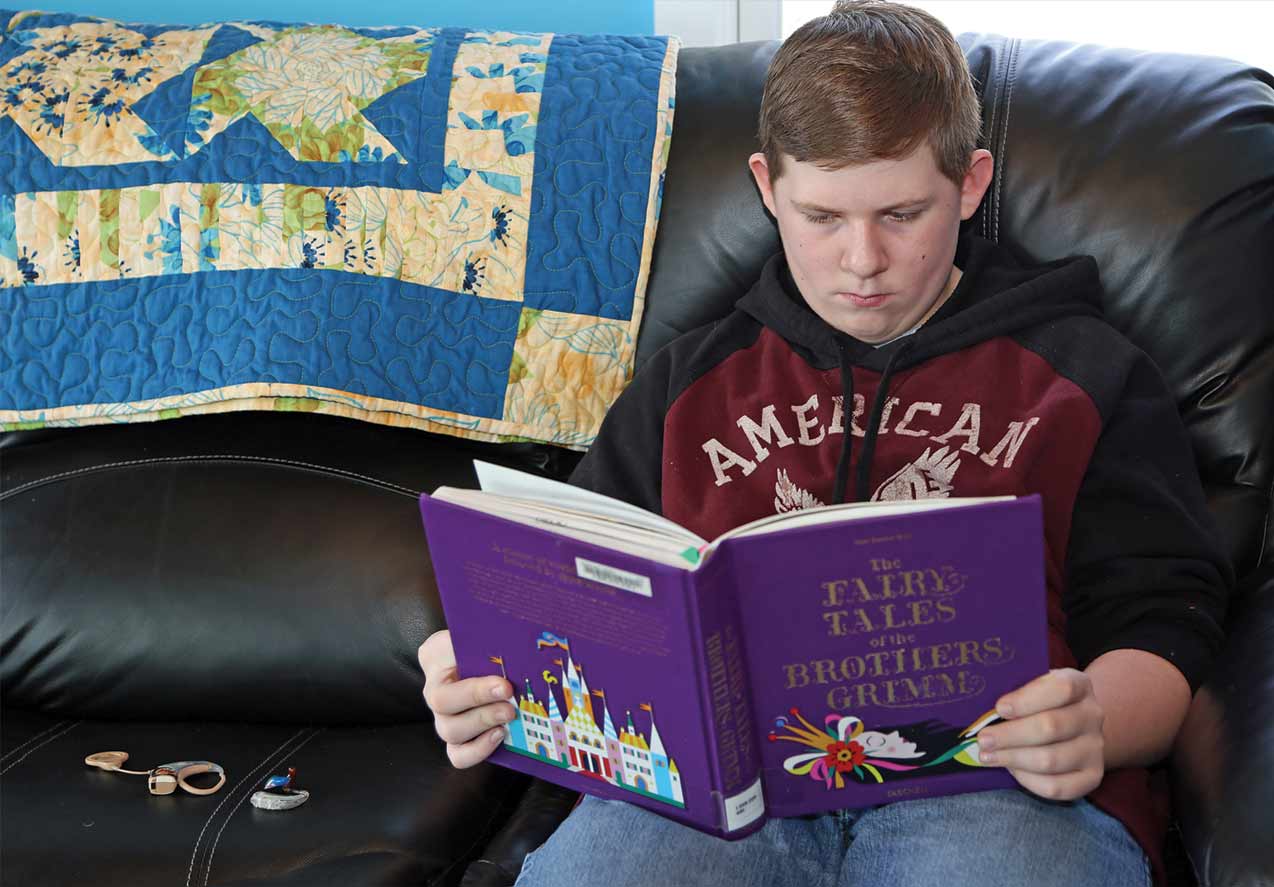

After a full day of school, sports and socializing, Andrew likes to enjoy the silence for a little while. The 12-year-old Central Square resident, who was born deaf in both ears, uses a cochlear implant device that was surgically attached to his brain nine years ago. That has given him the ability to hear others within close proximity.

He has worked hard to develop speech and become proficient at reading lips. He has been in a mainstream classroom since kindergarten, consistently makes the honor roll, and has excelled in lacrosse, says his mother, Mandy Zinger-Gutchess.

“He never considers himself different because of it (hearing loss),” Zinger-Gutchess says. “It is a lot of work on his brain, though. At the end of the day, he’ll take the devices (detachable portions) off, maybe play a video game or watch TV with close captioning. He likes that quiet time.”

Improvements in technology, teaching methods and attitudes have led to huge changes in how students with hearing loss are educated. Today, parents, educators and audiologists say Central New York children who are partially or profoundly deaf are allowed the same pathways as typical children without having to deny their true selves. Like Andrew, they, too, get a break from the noise once in a while.

Ann Elliot is an Onondaga Cortland Madison BOCES speech language pathologist based at the Park Hill School in East Syracuse. Since she began her career in the mid-1970s, she has witnessed a sea change in methods of educating children with hearing loss. Four decades ago, teachers, parents and some members of the deaf or “hearing impaired” (now an obsolete and unaccepted term) community discouraged sign language and pushed kids to learn speech instead. Residential schools for the deaf were commonplace.

“Sign language was a subculture,” she says.

Today, there is an emphasis on educating children based on their individual strengths, needs and interests. The total communication model—using any combination of sign language, speech, lip reading, visualization and technology like table computers—is the preferred method, Elliot says.

“The main focus,” she says, “is to get there however we can get there. Minor adjustments result in major gains for every child.”

Elliot mainly works with children from ages 3 to 5. The vast majority of them were diagnosed with hearing loss by age 2 and enrolled in the county-funded Early Intervention Program, which covers some of the costs for hearing aids. It’s extremely important to get the diagnosis, equipment and education plan in place early, Elliot says, because after age 5 the human brain becomes less efficient in developing communication ability if it is not getting input.

Erica Bird, a teacher of the deaf who also works at Park Hill School, says it is important to have young children with hearing loss interact with typical children as well as with children with other special needs in a classroom setting. Teacher aides, occupational therapists and physical therapists are also in the mix.

The typical kids benefit from helping out their peers and developing leadership skills. But, she emphasizes, while the program prepares children with hearing loss for mainstream classrooms, the students and their families can elect to remain in special education programs for as long as they’d like. Some kids prefer to stick with sign language through graduation.

“There’s a strong deaf culture in Syracuse,” Bird says. “Each child is unique and their needs are different. Maybe they have deaf parents and their home situations are different.”

That’s the case with the Walshvelo family of Liverpool. Parents Jodi and Randall were born profoundly deaf. Son Dylan, known as DJ, age 11, is deaf in one ear. Son Lamar, 9, has full hearing. DJ attends classes in Solvay, where he splits time between special education and mainstream classrooms. Lamar attends Elmcrest Elementary School in Liverpool. Both ski and participate in competitive sports. At home, the family communicates with sign language.

Jodi, who grew up in Minnesota, was mainstreamed through elementary school before attending a residential school for the deaf until graduation. Randall graduated from Altmar-Parish-Williamstown High School in Oswego County before continuing his education at National Technical Institute for the Deaf, an engineering college at Rochester Institute of Technology. While Jodi and Randall embraced the deaf culture at different points in their lives, they fully support today’s total communication model for their children.

“I prefer that DJ learns about the deaf culture as well, because his parents are deaf,” Jodi signs as interpreter Trisha Schwartz translates. “But we also want him to develop speech skills.”

“Whichever he does, he enjoys,” Randall signs. “Speech is his preference (at school) right now, and that’s OK.”

Here’s the typical arrangement for most public school districts: After a hearing loss diagnosis, referrals are made to the early intervention program, as well as preschool programs that help students to prepare to be mainstreamed at kindergarten or later, depending on what the family chooses.

Parents meet with their respective board of education to discuss a learning plan and available resources in the schools. Classrooms have an audio system for which the teacher wears a microphone that interfaces with whatever device the student uses. An aide works with the student in the mainstream classroom as needed, and in some instances the student completes coursework in an individual setting depending on his or her needs. Districts are expected to follow state guidelines for testing, which may allow the student more time to complete a task or for different test forms or devices to be used. Parents are expected to meet with the teachers monthly.

Elliot, the speech pathologist, cannot recall any instances in her four decades of teaching where a district said there wasn’t enough money or staff to accommodate a student with hearing loss. And while early intervention covers hearing devices for younger children, other programs fill in the gaps for the older kids. Aurora of CNY Inc., an organization that also serves the blind, provides hearing devices, which can cost upward of $2,000, for children over age 5. Aurora also helps older students with college applications, says Anne Costa, Aurora’s assistant director.

Whole Me Inc. is another non-profit agency that supplements school and county programs. It provides an after-school program where deaf children and adults from various communities come together, says Christine Kovar, program director. Whole Me also teaches sign language in the home.

“We meet the families where they are,” Kovar says. “If they want their kids to speak, we respect that. But we also encourage the parents to use sign language. It doesn’t matter if implants, supersonic hearing aids, smart phones or computers are involved. We want to give the kids a full toolbox. Technology is great when it’s working. But when it fails, they need something else.”

Arlene Balestra-Marko, a pediatric audiologist, works closely with school districts, county programs and non-profits that serve children with hearing loss. These days, she says, children as young as 3 months old can be fitted with hearing devices. The devices are digital and contain computer chips that reduce noise and are adjusted based on the root of the hearing loss within the ear. By contrast, the old analog devices were essentially microphones that did not have the ability to amplify speech sounds while turning down background noises.

Many hearing devices come with a credit-card sized streamer that allows the device to interface with computers, televisions and phones, she says. In addition, a few area schools have classroom audio systems that work with tablet computers so the words spoken into the teacher’s microphone appear in print.

“I think we’ll see more of that in the future,” Balestra-Marko says. “I also think they (devices) will get smaller, more kid-friendly.”

Families of children with hearing loss say they are thrilled with the available services, technology and support.

Scott and Jennifer Fiello’s daughter, Mary, was not diagnosed with hearing loss until age 2. At that point, the condition was severe, with 90 percent loss in one ear and 75 percent in the other. Fearing that Mary’s hearing would further deteriorate, the Fiellos worked diligently to help her develop language skills as quickly as possible.

Now 7, Mary uses hearing devices in both ears. She performs well in a second-grade class in the Baldwinsville school district and excels at competitive hip-hop dancing. She also plays indoor soccer.

“It (diagnosis) scared the heck out of us, to tell the truth,” Scott Fiello says. A pre-kindergarten program in the North Syracuse School District prepared Mary well for a regular classroom. In Baldwinsville, Mary leaves her mainstream classroom once a day to work on speech.

“It’s a loving atmosphere, which is a huge help,” Scott Fiello says. He and his wife are teachers in the Syracuse City School District and have experience in working with boards of education. At the beginning of this school year, Mary did a PowerPoint presentation for her class on her hearing loss and the devices she uses.

Similarly, the severity of 7-year-old Giovanna’s hearing loss was not known until after her second birthday. By starting preschool at age 3, Giovanna got on the fast track to developing communication skills, says her mother, Nicole Curro. Giovanna uses hearing devices and can also read lips. Her experience in the Liverpool School District has been challenging yet rewarding, her mother says.

“For her, making friends is a little difficult,” Curro says. “You have to tap her on the shoulder to get her attention.”

Giovanna completes spelling and math tests one on one with a teacher, and she also gets speech therapy services. But everything else, including physical education class and homework, is the same as her classmates. Her grades are excellent because in the past she enrolled in summer school to keep up with the curriculum.

“This year,” Curro says, “she’s not going to have to go because she’s made so much progress.”

At Home with the Walshvelos

Jodi and Randall Walshvelo, a deaf couple who live in Liverpool, have one son with severe hearing loss (DJ, age 11) and another with full hearing (Lamar, age 9). Jodi and Randall met at a deaf social event in Chicago and later moved to Central New York. Jodi works as an integrative community specialist at Arise Inc., while Randall is a full-time student at Le Moyne College. He was previously employed as an engineer but is now pursuing a career in special education. Lamar attends school in the Liverpool district, and DJ attends a program in the Solvay district that blends special education with mainstream classrooms. With the help of sign language interpreter Trisha Schwartz, the family recently discussed their experiences of living in two different worlds with a reporter.

Family Times: What were your thoughts when your first child was born with hearing loss?

Jodi: My mom has deafness in her family. I have a brother who is deaf and two sisters who can hear. We kind of expected it.

Randall: My family is hearing except for me and my sister. With DJ, we were happy that we’d have that connection. The nurse said, “I’m sorry: Your son has hearing loss.” We said, “We’re not sorry. We’re just happy he’s healthy.”

FT: What were your thoughts when your second child was born with hearing?

Randall: We were delighted that he has 10 fingers and 10 toes.

FT: Talk about your experience in schools

Jodi: I was mainstreamed up to sixth grade. It was a small program in a small town in Minnesota. Then my parents decided to put me in a residential school for the deaf. They gave up their jobs to move closer to the school to see me and my brother. I stayed until I graduated. I was on the basketball team. I was a cheerleader. I was involved with political activities. I had a great experience.

Randall: I’m from Williamstown (Oswego County). I grew up in the hearing world. I was one of two deaf kids in school. I went to RIT (Rochester Institute of Technology). That’s when I got involved in the deaf community. I was able to function in both worlds.

FT: Talk about the dynamics of your family. How do (your sons) handle being in two worlds?

Jodi: Sometimes they both sign, sometimes they both talk. They know each other’s speech. There are no rules about how they should communicate with each other in the house. But at the dinner table, we want to be included in the conversation, so no devices.

Randall: We don’t want to impose anything on them in their own communication. We encourage them to sign when they are with us, but we don’t enforce it.

FT: What responsibilities, if any, fall to your sons?

Randall: We don’t depend on them for anything. In a restaurant, even, we usually work it out without them. We feel it is important to be independent. We want them to enjoy their childhood.