Few things are cuter than children and pets. The pure joy each finds in the other makes getting a pet appealing to many. Yet getting a pet is about far more than cuteness. Adopting a pet brings rewards and risks for a family that bear serious consideration before the first visit to a shelter, breeder or pet store.

“A puppy with a child can be a beautiful experience,” says Kathy Gilmour, executive director at Helping Hounds, a dog adoption service in DeWitt. “And it can also be an absolute nightmare.”

The benefits of having a pet may seem obvious to those who have animals they love. Beyond having someone to greet you when you get home, pets can help teach children lessons about life and responsibility. In addition, studies have found children in homes with dogs are physically more active and that babies raised in homes with pets are significantly less likely to develop allergies to that type of pet.

Related: Cats vs. Dogs: Resources for tips on how to find the right family pet

Experts in animal companions interviewed for this story agreed that any discussion about bringing home a pet needs to start with a frank self-assessment. Are you ready for a pet? Do you have the space? Do you have the time? Do you have the money—not just the money for the purchase or adoption, but also the ongoing expenses of food, grooming, veterinary care and other costs.

What about other people in the household? Are they ready for the disruption a pet can cause and the energy a pet may require? If you rent, is the landlord OK with you having a pet? Get these issues settled first.

“Then, it is time to be introspective and to look at your lifestyle,” says Pamela Edwards, a veterinarian who practices in Syracuse. If you are a couch potato and you think getting a high-energy pet will help you turn over a new leaf, “It’s unlikely to happen,” she says. “It lends itself to a bad partnership.”

Likewise, consider how stressed you and your family are at the moment. If the new pet requires time for training or cleaning up afterward, will you be able to handle it? What about the time and effort needed to teach children how to properly handle the pet?

However, don’t let yourself be intimidated by the prospect of pet ownership, says Christine McNeely, executive director of the HumaneCNY shelter in Liverpool. McNeely says when she was small, her parents sought to adopt a kitten but were rejected because her mother worked outside the home.

“She was turned down because she was a working mom, because no one was going to be home all day,” McNeely recalls, still finding it hard to believe. “Any family has the potential to be a great pet owner.”

Gilmour, the Helping Hounds director, says any family considering adding a pet to the home should look at the pet’s energy level, how house-broken it is and how well it gets along with others—including other pets, if there are any.

What about breed? There are 187 breeds of dogs recognized by the American Kennel Club—from Affenpinscher to Yorkshire terrier—but breed alone won’t tell you what dog is right for your family, Gilmour says.

Some breeds have reputations; think of lovable golden retrievers or docile Basset hounds. But dogs are individuals and can be quite different from others of the same breed, says Danielle Basciano, of CNY Pet Training and Behavior. “We usually call it ‘a study of one,’ where it really boils down to the individual animal,” she says.

Edwards agrees. “I think that the individual traits outweigh the breed traits.”

That’s why Helping Hounds and other pet adoption organizations often send adult dogs to foster homes before they are available for permanent adoption. At a foster home, the dogs can be observed and the foster “parents” can offer some insights into what home might best suit the individual dog.

“It gives us a glimpse,” says Gilmour, whose organization has found homes for about 5,500 dogs since she became executive director in late 2012. With that look into the dog’s personality, she says staff and volunteers try to steer families to dogs they think would be a good fit.

Ronan Drozd, 14, of Fayetteville, has been raised with dogs. His mother, Janet, had an Irish wheaten terrier named Doolin when Ronan was born. Doolin was welcoming to the baby, Janet says. “He was fine. Wheatens are people persons,” she adds. “They are very sensitive, the wheaten. They wouldn’t hurt a human.”

Doolin died when Ronan was in first grade. It was a very sad time, Janet recalls. They quickly found Clifden, another Irish wheaten terrier. Four years ago, they added Rocket, a West Highland white terrier.

Ronan feeds the two dogs when he gets home from school, one of his chores since sixth grade. “He is very responsible about feeding them and letting them out,” his mother says. Taking on those tasks has taught him a level of responsibility, she says.

Janet taught Ronan by modeling behavior and reminding him of his responsibility to the dogs. “A lot of reminders,” she says. When he would forget, she would remind him the dogs were depending on him.

“They can’t go to the refrigerator and get food,” she would tell him. “Put yourself in their shoes. How would you feel if you had no control over your food?”

“Now it is something he does without reminding,” she says.

And, she believes, caring for the dogs has taught him about kindness and its rewards. “They like to be with Ronan.”

Ronan isn’t responsible for all the dog-related chores. Janet cleans up after the dogs—“I do that myself. It’s just too gross”— and gives them their baths.

The Cat Fanciers’ Association recognizes 42 breeds of cat, but Edwards says she doesn’t see a consistent personality among breeds. “In cats, I find that in all breeds, there tend to be really sweet ones and ones that tend to be more aloof. I will say that in domestic shorthairs, I find that coat color plays into their behavior. I find that calicos and red-headed cats tend to be more feisty.”

The friendliest? “Black cats and tigers tend to be really family-oriented and sweet, in my experience,” Edwards says.

If you are considering bringing a cat of any color into the family, McNeely and Basciano say to visit with the animal first and watch its body language for clues to its personality. A cat that approaches a human is likely to be more affectionate—if that’s what you’re looking for.

Kristin Russell-Miller’s daughter, Emma, has been raised around cats and dogs and even around foster cats that her family cared for as they were awaiting adoption. Now nearly 7 years old, Emma has learned enough that she joins her mother, a certified pet trainer with CNY Pet Training and Behavior, in front of classrooms for dog-safety presentations.

“Emma has gotten all of those lessons since birth,” Kristin says. “Teaching her is more about teaching her to be respectful of animals and to listen to them.”

“Listening” means understanding the body language of animals, Kristin says. She explains that cats give pretty clear signals before they bite or scratch. For instance, cats will flatten their ears and lash their tails to indicate they are annoyed.

Even though Emma has been educated and is very compassionate—“She understands pets have feelings, too,” Kristin says—there are rules to protect Emma, her friends and the pets. Pets and children are not allowed to be together without adult supervision, Kristin says. Cats must be allowed access to an “escape route,” to someplace they can feel safe. Plus, Emma knows not to chase cats or pick them up if they don’t want to be picked up.

“Put yourself in the animal’s shoes,” her mother says. “Have you ever been hugged by a stranger?”

Emma also teaches her friends how to deal with an excited dog: Be a tree. “If a dog ever jumps on you or makes you nervous, you should stop moving because running kids are something that increases a dog’s arousal,” Kristin explains. “Emma will teach her friends to be a tree by putting her hands under her armpits and kind of standing still, looking up and away. The more boring you are, the quicker the dog will lose interest and move away.”

Related: Fur Babies: Can you compare pet ownership to parenting?

Edwards notes that although children can learn lessons from being raised with pets, it is wrong to expect them to take on the level of responsibility some promise while pleading for a dog or cat. The ultimate responsibility remains with the parent, not just for the care of the animal, but for teaching children to respect the pet.

Sometimes families discover that a new pet is not working out. “Holy cow, this is a lot of work,” is something Gilmore hears from some families. Others are shocked by the first vet bill. Or maybe the new pet doesn’t get along with pets already in the home.

Edwards offers a rule of thumb: If things don’t seem to be working out within the first two weeks, it might be better to return the pet. Waiting longer to move on from a pet that is not a good match can be much harder on the family, and the animal.

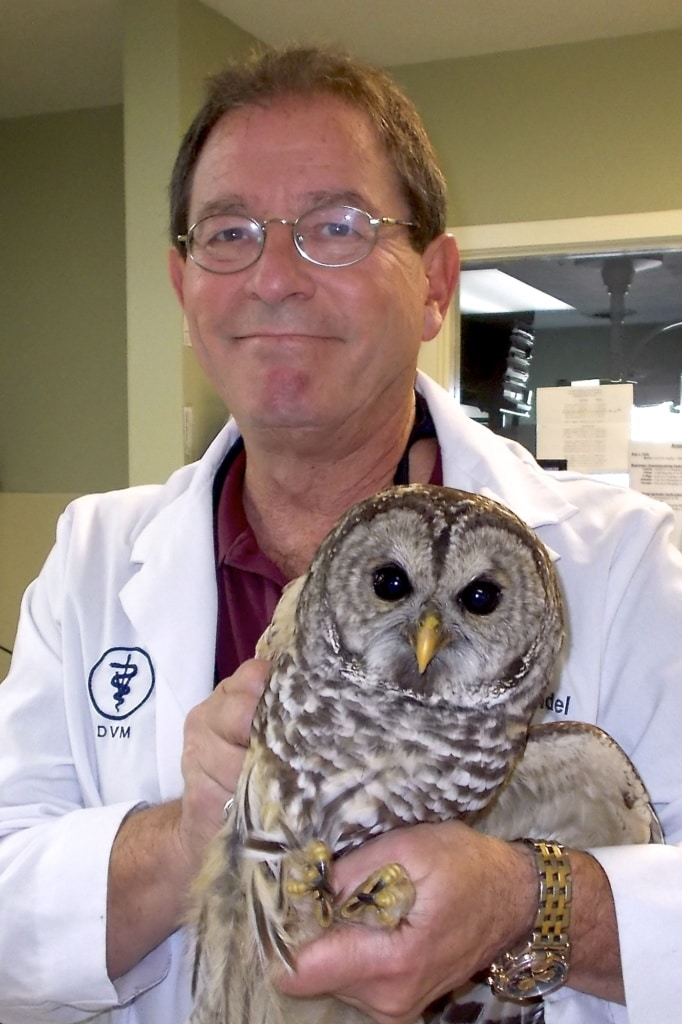

Edward Spindel, a veterinarian at Animal Ark Veterinary Hospital and Kennel in Baldwinsville, says young children can do well with docile pets that can tolerate some handling, such as rabbits and guinea pigs. Parents can help instill good personal habits, for instance, by teaching children to wash their hands whenever they’ve been handling the animals.

Whatever sort of pet a family brings home, Spindel says there is value in observing and caring for it. While there certainly are lessons to be learned, “Children also can develop an appreciation for other animals that share our world.”

Trendy and Exotic Animals

There are fashions in pets. Purse dogs really are a thing, and certain breeds of dogs and cats have had moments of great popularity.

“I find that there are some dog breeds that tend to be fashionable at times,” says Pamela Edwards, a Syracuse veterinarian. While golden retrievers and Labrador retrievers were tops for years, she says right now, “The French bulldog and the Australian shepherd seem to have swept the industry.”

Beyond cats and dogs, exotic pets have achieved a level of popularity. Exotics include birds, reptiles and small mammals such as sugar gliders and hedgehogs.

“In a nutshell, my message would be: Do your homework and really look into it,” cautions Mark Irwin, a professor at Jefferson Community College, in Watertown. A doctor of veterinary medicine, his household includes two goats, a cat, some show rabbits and three snakes.

He notes that some exotic pets aren’t interested in “cuddling,” so keeping them might be more of a hobby than a companion experience.

Exotic birds can live for decades and tortoises can live more than a century, requiring long-term-care planning, even making provisions in one’s will. Snakes and other reptiles may require unusual diets—live mice or insects, for instance—and medical care for unusual pets may need specialized veterinarians.

Edward Spindel, a veterinarian who has practiced in Central New York for more than 30 years, says small mammals are very popular. “I see a lot of hedgehogs,” he says. He notes that the quilled animals aren’t particularly good for families with young children. “A 3-year-old is not going to handle it,” he says.

Monkeys or primates of any kind are not appropriate pets, the London-based Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals declares. “They’re highly intelligent animals with complex needs that can’t be met in a home environment,” the group says.

Irwin agrees. “They look so cute and playful, but in your home, they would be a disaster in many cases.” Noting their remarkable strength, quickness and ability to wreak havoc, Irwin says of monkeys, “They are like toddlers, but in three dimensions.”

Early in his career, Spindel used to see a pet monkey nearly every week. Nowadays, he sees maybe a half-dozen in a year. “People got smart. They are not good pets.”

Irwin provides another option for spending time with exotics: He heads Jefferson Community College’s zoo technology associate’s degree program, a two-year course of study designed to prepare students for careers as zookeepers or zoo educators.